Alive! and Well: Celebrating SC Johnson’s Spirit of Adventure Sixty Years After its World’s Fair Debut

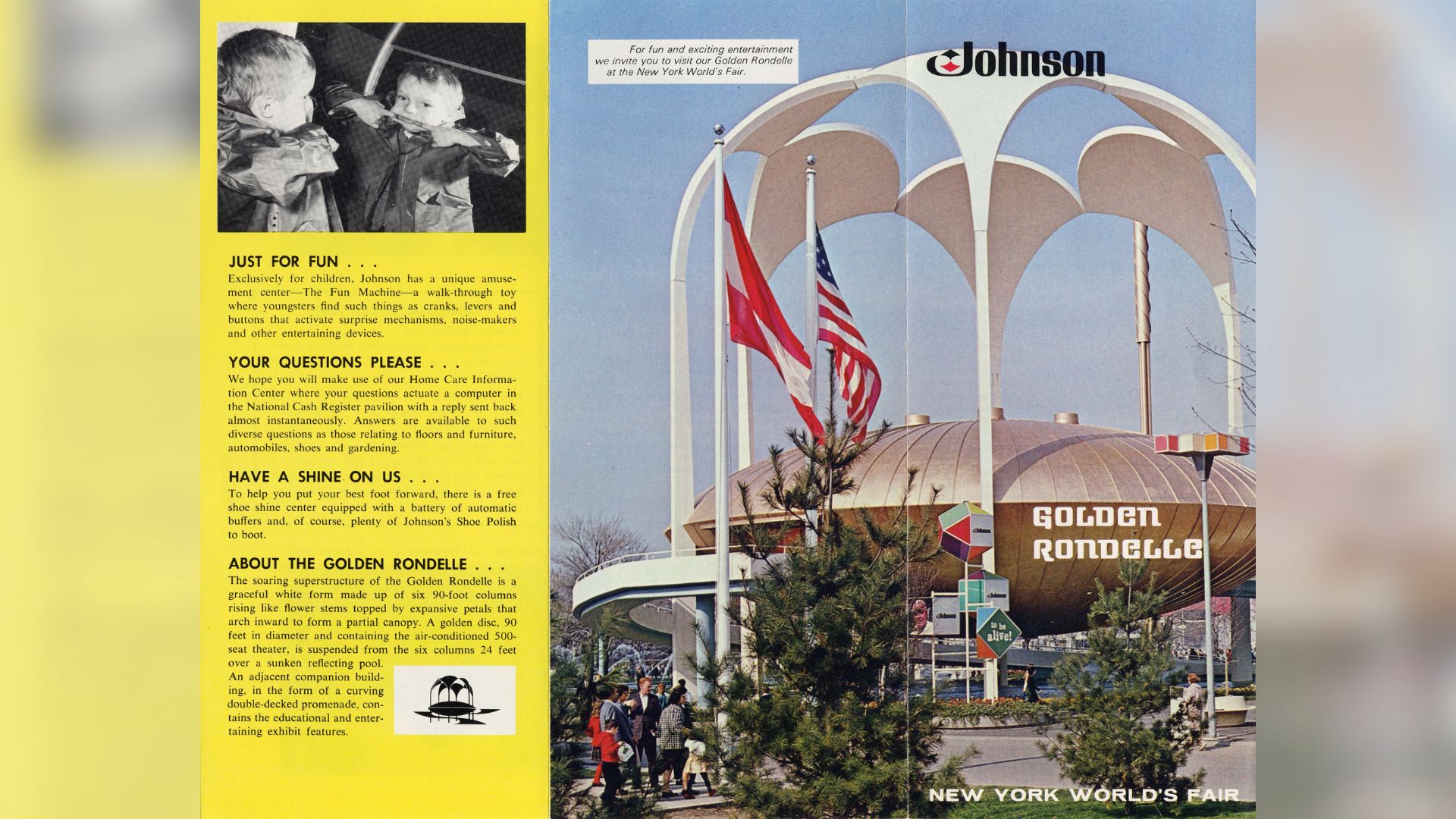

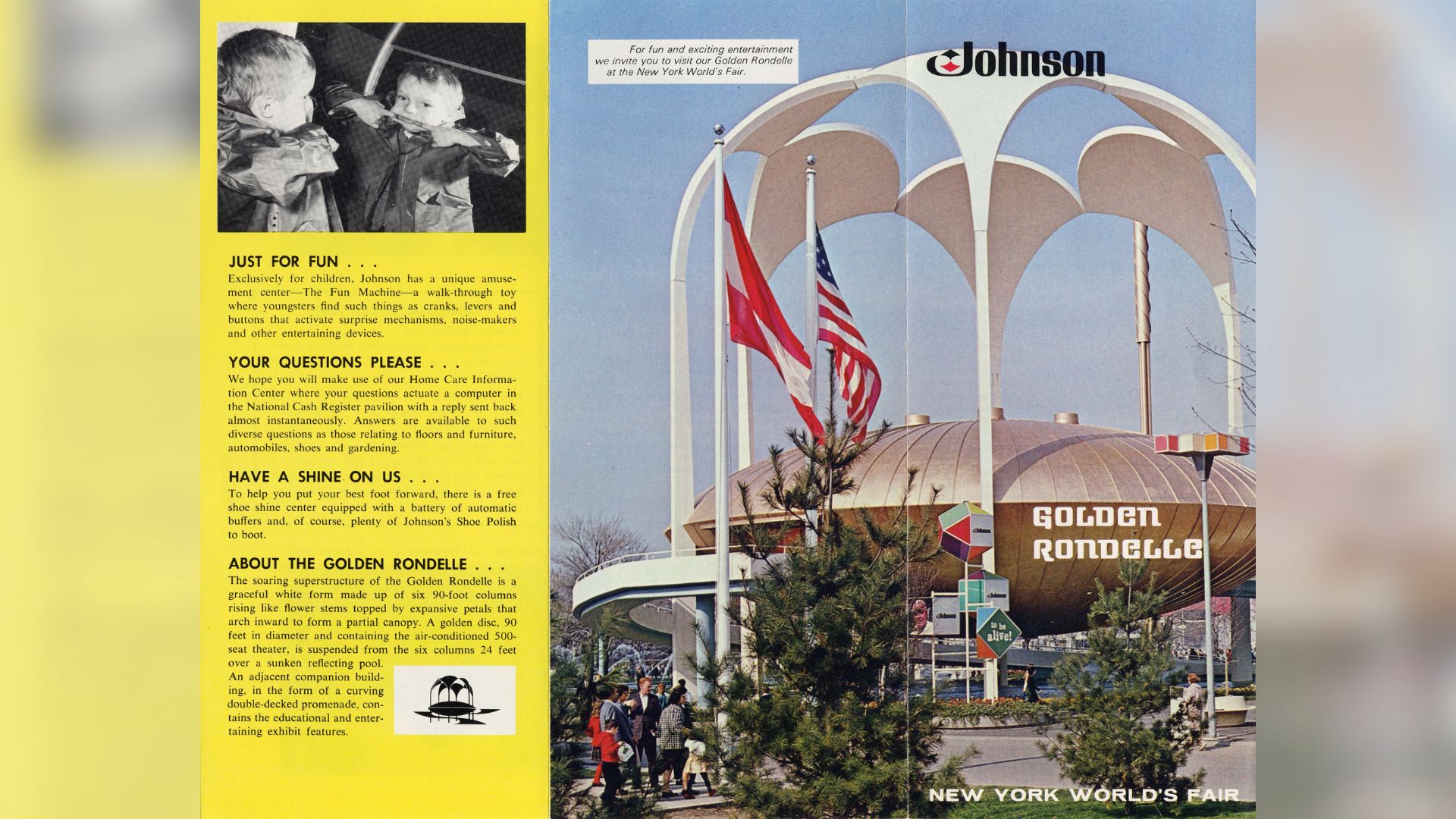

Fairgoers were immediately drawn to a gold, circular building on the rainy spring morning the New York World's Fair opened on April 22, 1964. The building, held up by six concrete columns, was a makeshift sun parting through the gloomy clouds as they lined up, craning their necks to get a glimpse inside. Nothing could dampen their excitement as the sound of Mozart mingled with the falling rain around them. The sweet scent of Belgian waffles still filled their noses as they waited to enter what would become one of the fair's most popular exhibits: The Johnson's Wax Pavilion and the film To Be Alive!

By the time the fair closed in October of 1965, more than five million visitors had gone through the company’s pavilion and seen the 18-minute film they produced. Some had even waited up to two hours to watch it. Former U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower called it “... a most imaginative film and very beautifully done. It shows the world through the children's eyes, where there is no room for prejudice or arrogance.”

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the fair and the debut of the widely celebrated film, and today, it continues to highlight SC Johnson’s commitment to making the world a better place today and for future generations.

In planning the pavilion and film, the company’s third-generation leader, H.F. Johnson, Jr., had taken the fair’s theme, “Peace Through Understanding,” to heart and wanted to bring something that celebrated life rather than just tout the different products SC Johnson offered. A visionary man, H.F., Jr. was unafraid to take the company in directions no one expected from a simple floor wax business out of Racine, Wisconsin. SC Johnson’s executives and vice president Sam Johnson, who was H.F., Jr.’s son, were very hesitant to put over a third of the company’s advertising budget into this project. Sam Johnson told his father, “It isn’t going to sell any more of our products” and would most likely “hurt the business.” H.F., Jr. responded, “Sam, some decisions are only for the brave.”

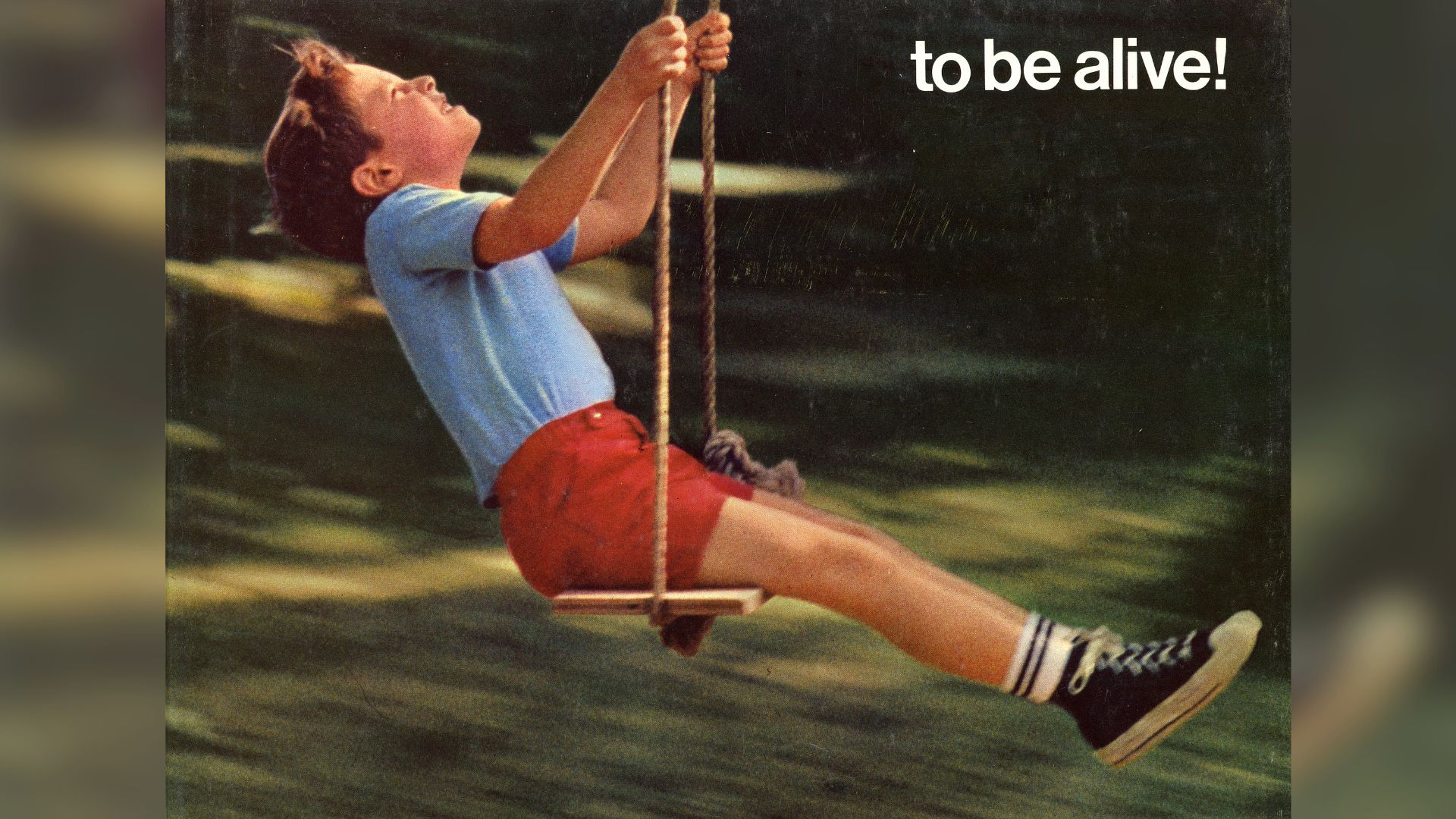

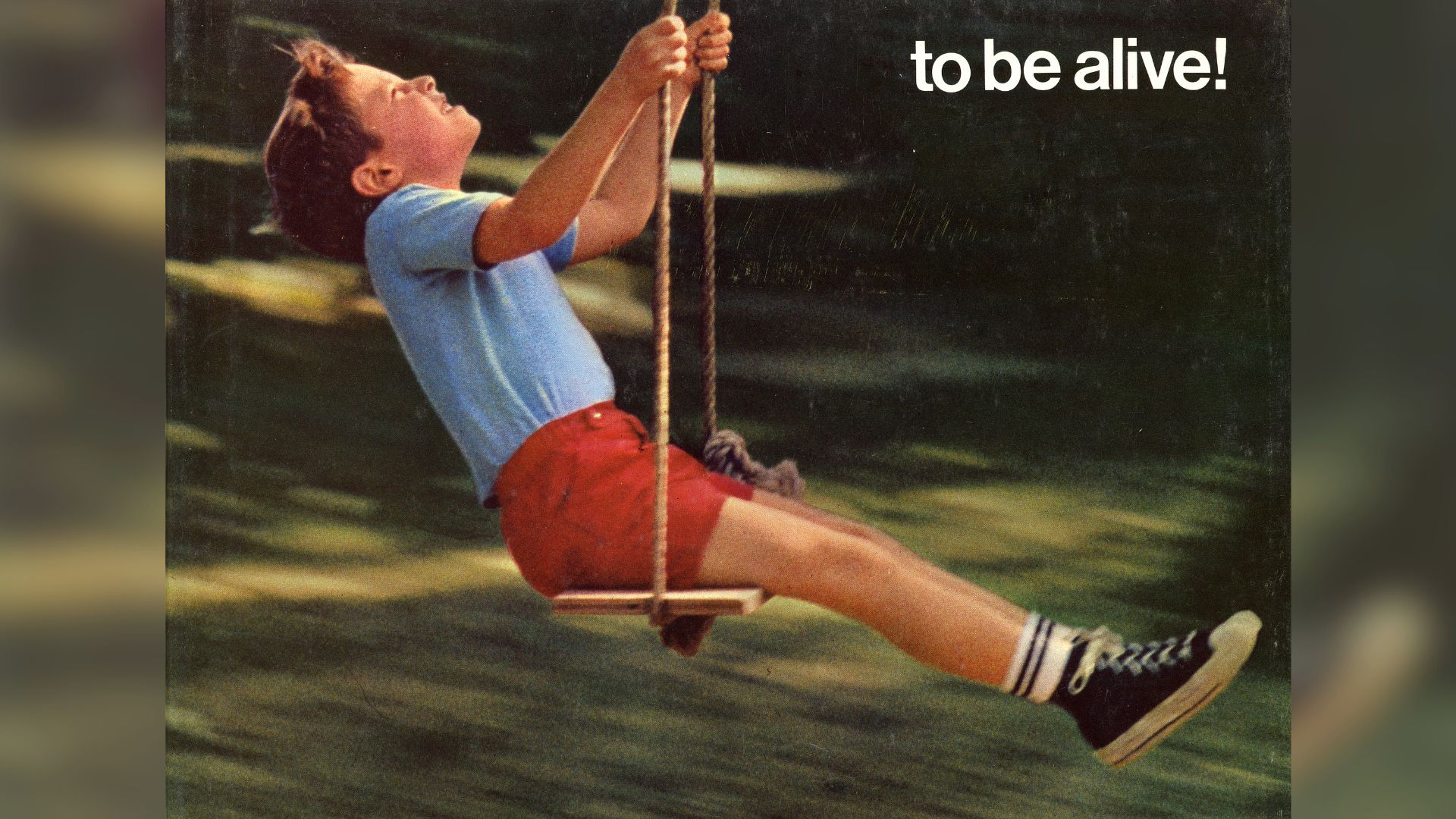

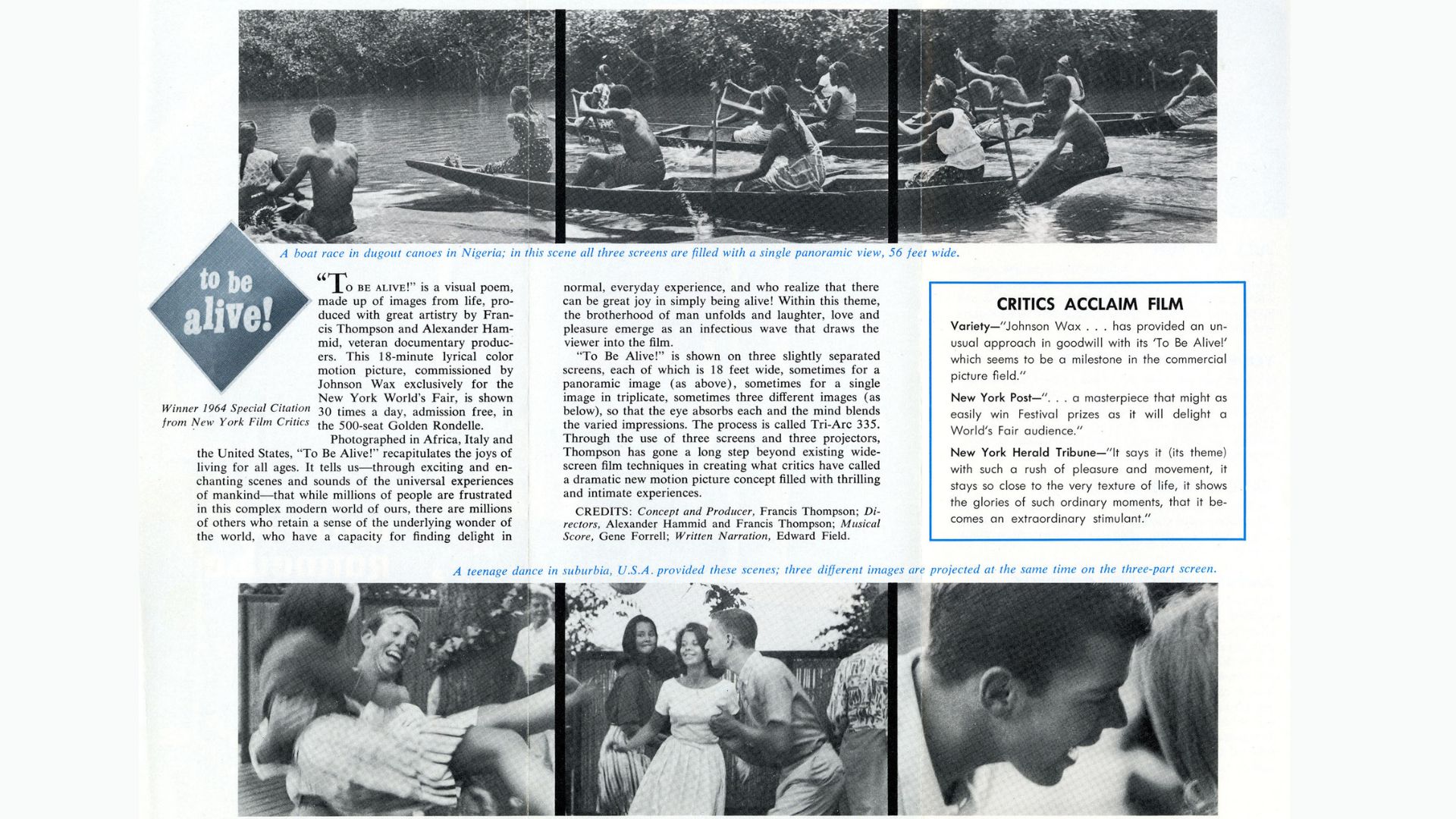

H.F. Johnson, Jr. gave directors Francis Thompson and Alexander Hammid complete creative control over the project, resulting in a film highlighting the little joys in life that children all over the world, no matter their culture, experience as they grow into adulthood. The official guidebook from the fair described To Be Alive! as showing the daily lives of people around the world, where “they grow up, fall in love, work, play and grow old, demonstrating that ‘men everywhere share at the deepest level the same drives, dreams, foibles.’”

Stills from the 1964 film To Be Alive!

A Showcase of Cultures

The New York World’s Fair in 1964-65 was unique for many reasons. First, the Bureau of International Expositions, which was the international body that sanctioned world’s fairs, did not endorse it. To afford the cost of the New York World’s Fair, its organizers wanted the fair to run for two six-month sessions and planned to charge exhibitors a fee for constructing their pavilion. Both conditions were against the Bureau’s rules, who proceeded to request its member nations refuse the invitation to participate in New York.

This refusal was the catalyst for the second reason the fair was so unique. With the absence of many European nations, there was now space for smaller, non-European nations to participate. Countries around the world, from Morocco to Venezuela, were able to attend and share their language, food and culture with U.S. fairgoers. More than 60 different nations ended up participating in the fair, and for many of them, inclusion was significant as they were still in their infancy. Thirty nations even created commemorative postal stamps to celebrate their involvement. Some participating countries, like Guinea, had been established less than ten years before the fair, and others, like Malaysia, were only a year old.

As a result, the New York World’s Fair became a memorable example of the intersection of cultures that was to come as the United States’ population and demographics increased. In the three decades following 1965, more than 18 million immigrants from around the world would come to the U.S.

Delicacies like Belgian waffles “sold like hotcakes” at the fair as many were tasting them for the first time, and many international pavilions offered dining forays that most Americans had never experienced. Japan’s pavilion served its food on low tables and prohibited shoes, and the Indonesian pavilion had traditional dancing and music playing while people ate.

Man's Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe

Along with highlighting many different countries around the world, the 1964-65 World’s Fair also became a showcase for the incredible technological advances the world was making at the time. The organizers aptly dedicated the fair to “Man’s Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe.” NASA exhibited several full-scale models of a rocket, its engine, and even the first two capsules scientists were developing to send astronauts to the moon.

Jetpacks and “picturephones” were also introduced during the 1964-65 fair. “Picturephones,” as Bell System called them, were the first iteration of video conferencing. The phone was connected to a small video screen where the caller could see the other person on the phone. Picturephones were also set up in Disneyland in California so fairgoers could see and talk to park visitors on the other side of the country.

Even the iconic Ford Mustang was introduced at the fair. Mustang convertibles and other late-model Ford cars were on a moving conveyor belt for fairgoers to hop in and ride back to the age of the dinosaurs. This “ride” was created and narrated by Walt Disney especially for the fair. Well-loved Disney attractions like “It’s a Small World” and the “Carousel of Progress” were also created for the fair, as part of the UNICEF pavilion and the General Electric Pavilion respectively.

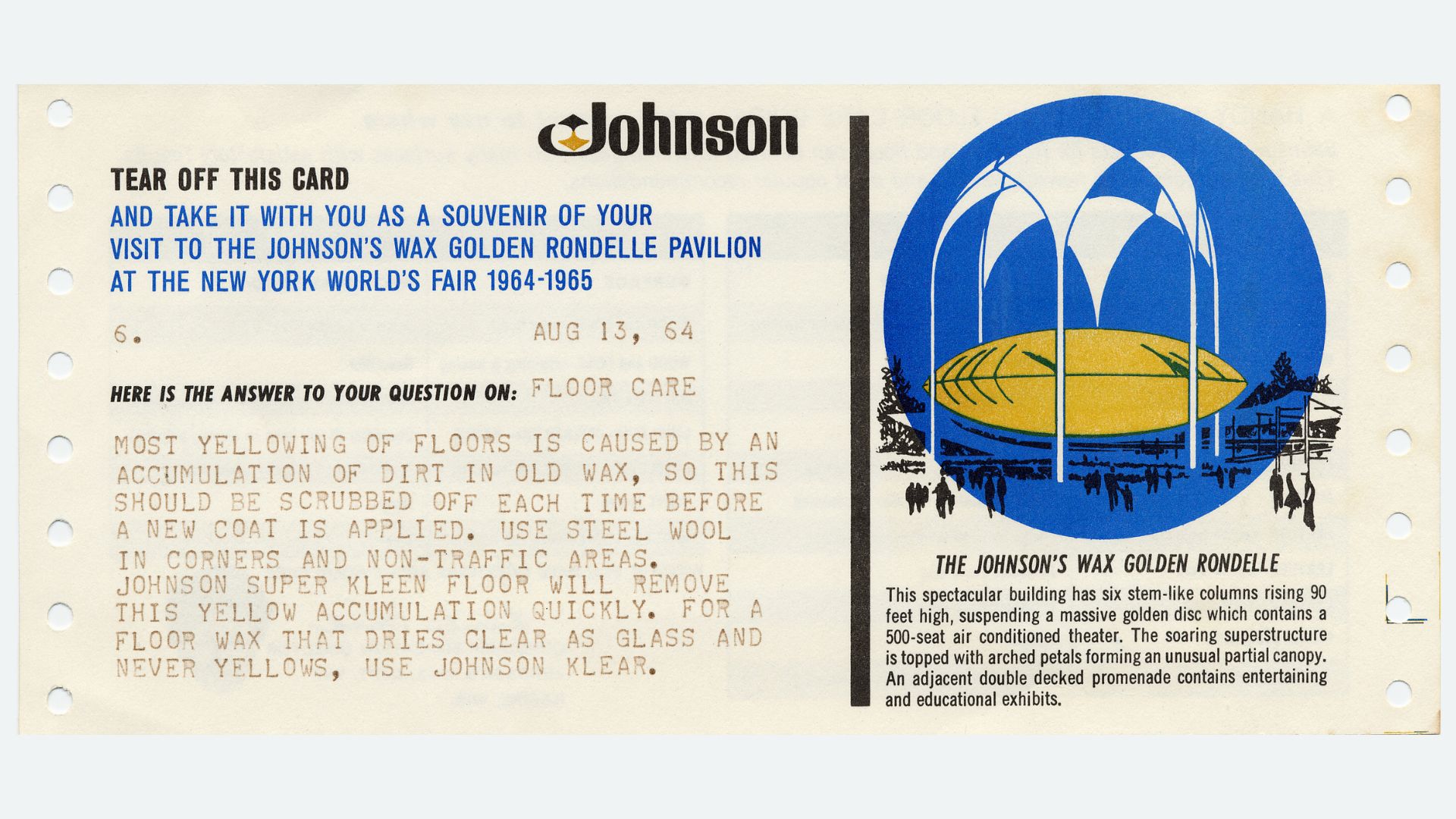

SC Johnson’s film To Be Alive! could be considered another example of technological advancement at the fair. The film was one of the first to use a multi-screen format instead of the traditional one screen. Inside the Johnson Wax’s pavilion, 500 people at a time could watch To Be Alive! play on three 18-foot screens separated by a foot of space. In 1966, the film’s directors even won an Academy Award for it.

After the Fair

After two six-month runs, bringing in over 50 million visitors, the New York World’s Fair ended. To keep the adventurous spirit of the company alive, SC Johnson dismantled the pavilion and brought it home to Racine. At its global headquarters, it was renamed the Golden Rondelle Theater and redesigned by the Taliesin Associated Architects to fit in with the company’s Frank Lloyd Wright-designed buildings. Today, the Golden Rondelle Theater acts as SC Johnson’s connection to the Racine community and the world. It is home to the company’s campus tour program, community interest programs and Kaleidoscope Education Series. The series provides STEM-based programs for children of all ages at no cost.

Since it opened in 1967, the Golden Rondelle Theater has held screenings of the film, though it was reduced to a single screen. In 2004, when the film and the fair celebrated its 40th anniversary, SC Johnson’s fourth-generation leader, Sam Johnson, restored the film to the original triple-screen format.

Today, To Be Alive! is available for the public every weekend and is part of SC Johnson’s campus tours that over 1 million people worldwide have taken. While there aren’t any Belgian waffles or classical music, the campus architecture, theater and film continue captivating crowds and inspiring future generations just as it did in 1964.